The rising tensions between Europe and Russia in the past months have seen an unprecedented increase in sanctions from the Bloc towards the Russian Federation. The latter has become the most sanctioned country in the World, mechanically affecting trade. Amongst the sanctions, the question of Russian gas has been central in the public and political debate. It is known that Europe uses Russia’s gas, and Russia gladly takes in the euros from that exchange. In the light of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the question of cutting completely any gas input is on the table.

Germany, which for a long time has refused to back any retorsion measures against Russia for economic reasons, has suspended the NordStream 2 certification, blocking any gas intake. The gas flow in NordStream 1 has slowed down as well amidst lower demand of Russian gas. The Yamal pipeline (going through Belarus) has even seen a reverse flow for a moment. However, the Brotherhood and Soyuz (meaning “union”) pipelines going through Ukraine have maintained their flow. Despite the war and the sanctions, Europe continues to import gas and pay Russia for it, and according to Bloomberg, Gazprom continues to pay Kyiv for the right to cross Ukraine.

The reality is that Europe didn’t cut out Russian gas. But could we cut out entirely from it?

Russian gas and petroleum imports in Europe

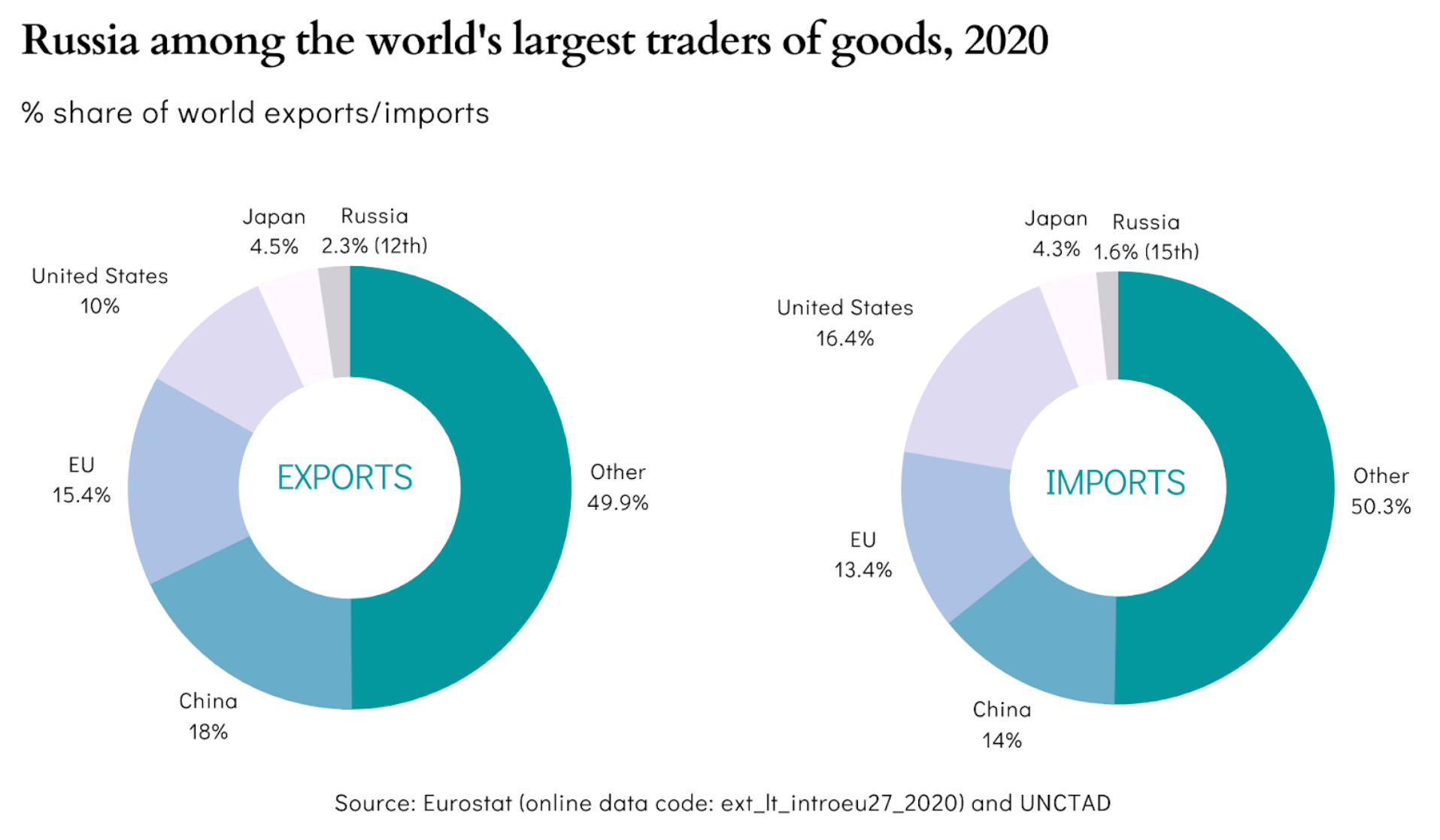

To answer that question we need to first take a look at the data available to see what the trade situation is. The EU is relatively dependent on Russia as a partner, with the Federation being the 3rd largest exporter with 7,5% and 5th largest importer with 4.1% according to Eurostat.

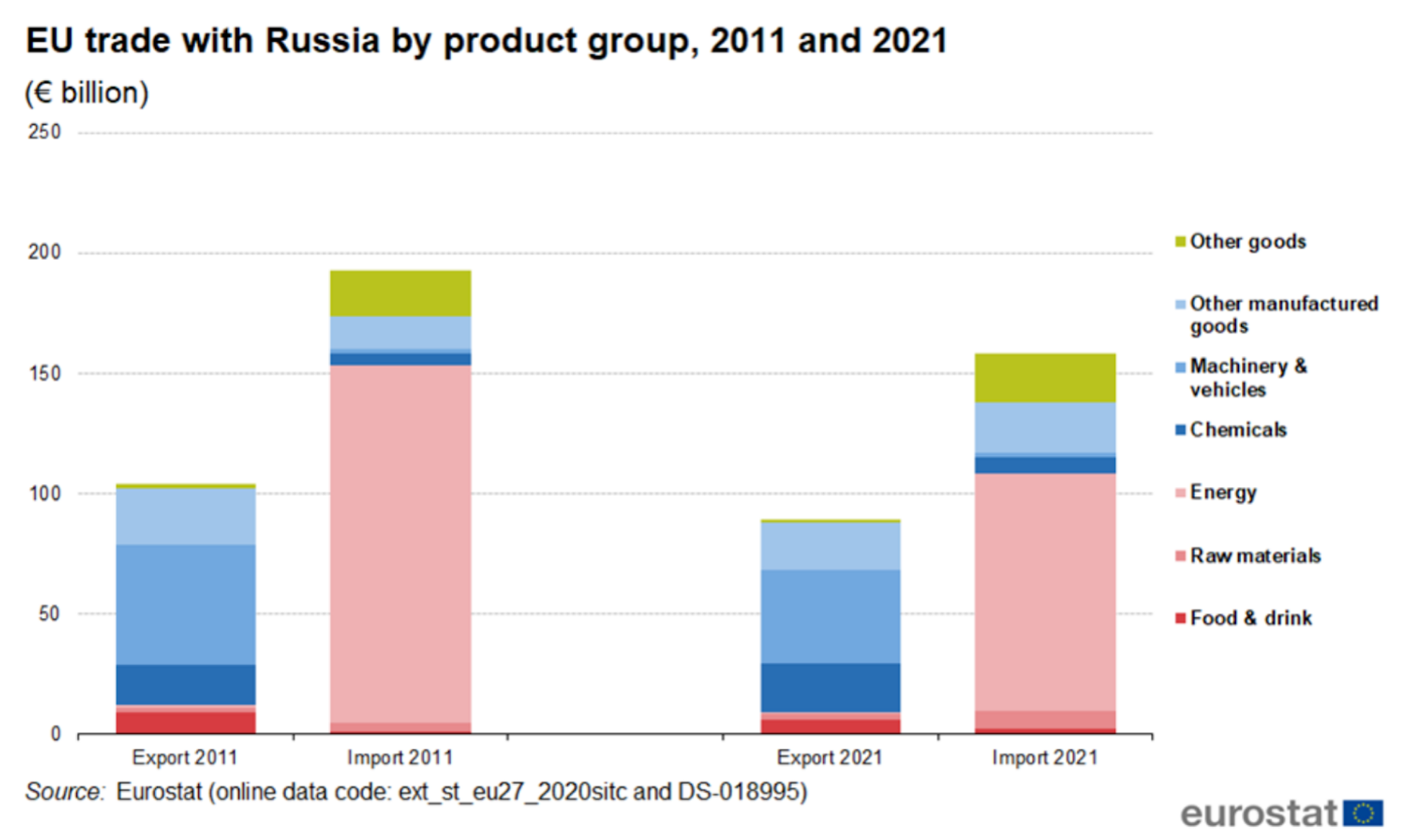

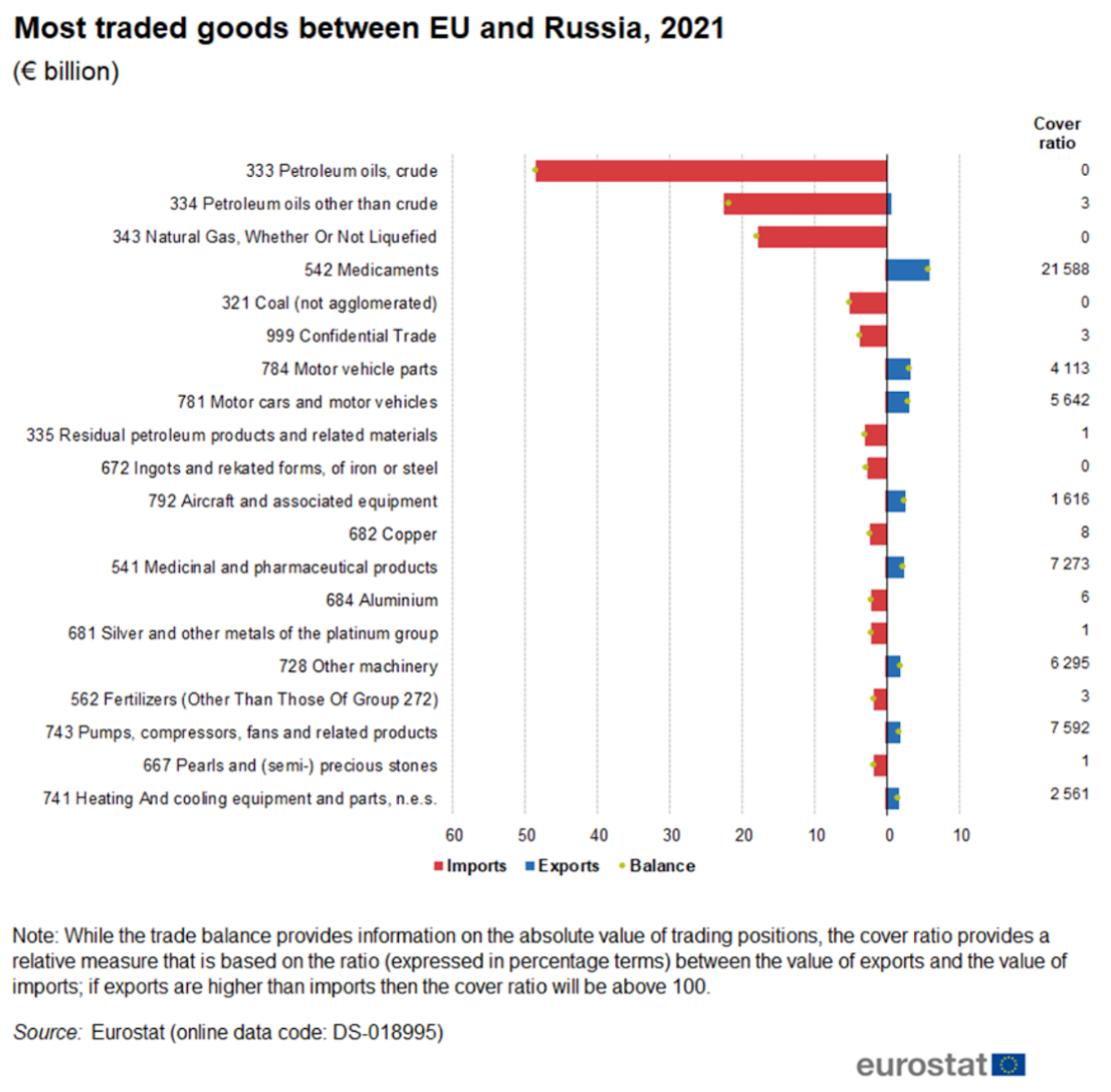

When focusing on trade with Russia, the vast majority of imports consists of energy-related products. Cutting down on such an import would represent a significant loss in terms of natural gas and crude petroleum imported for Europe, and in terms of revenue for Russia.

Finally, the graph above describes the imports and export balances of the EU with regards to Russia, with the latter being specialised as a major oil and gas provider. The commercial balance is massively in favour of Russia, meaning the EU needs its products, but they need the EU’s money in exchange.

The example of Czech Republic

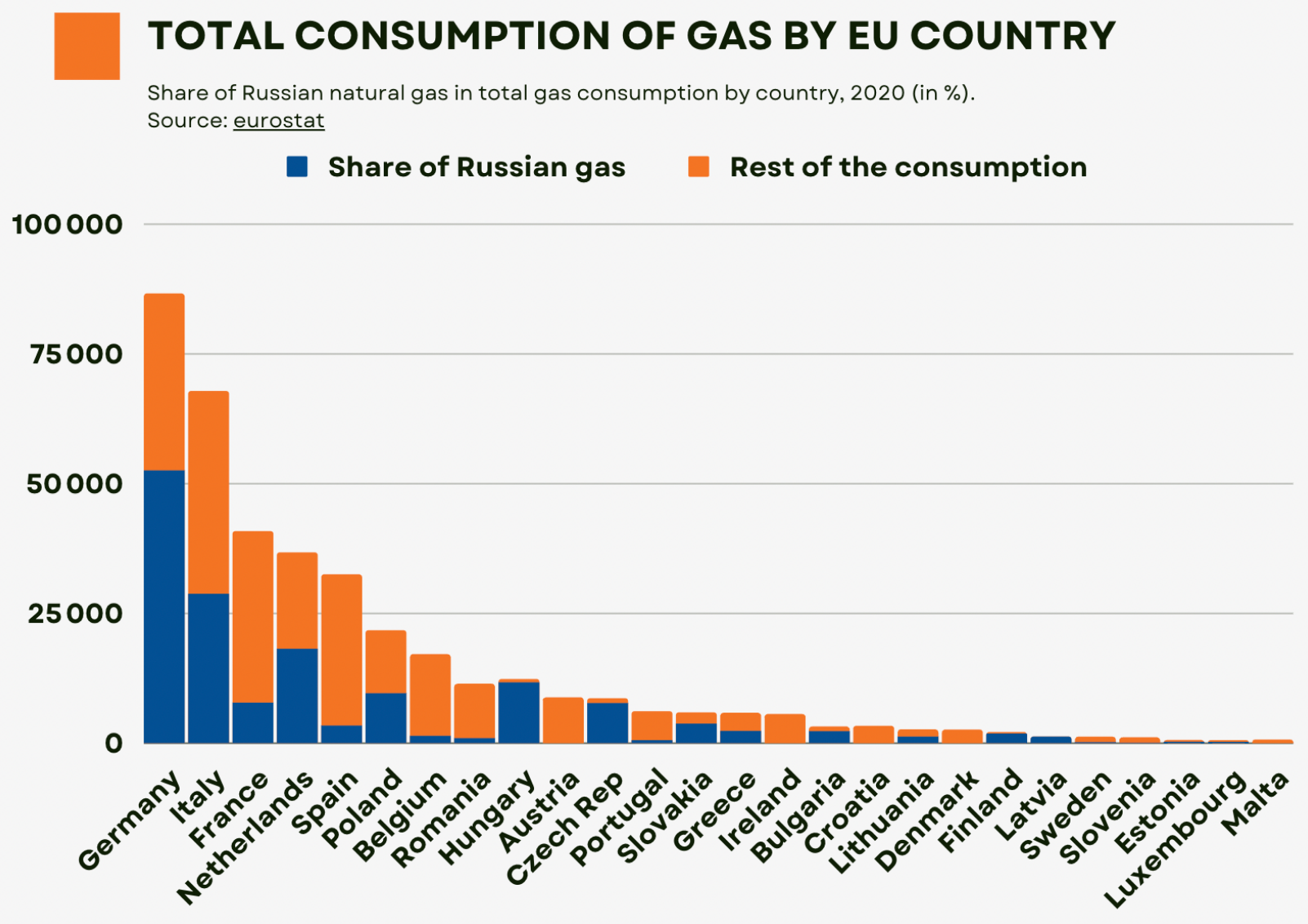

Europe is not in an ideal position but it is not equal for every country in the Union. Countries such as France rely mostly on nuclear power, making russian pressure on gas weak to none. However, in Eastern European countries such as Czech Republic, the situation is more delicate, as the majority of their natural gas and about 50% of their crude petroleum was imported from Russia in 2020.

Reducing the ties to Russian natural resources in the short term seems incredibly difficult, if not impossible, as they must look for new partnerships with other countries and risk getting entirely cut off from Russian supply.

According to CZSO, in 2020, 60,1% of the value of Czech imports from the Federation of Russia were for crude petroleum and natural gas. Even if natural gas and petroleum importations decreased by almost 50% from 2019 to 2020, it still represents a large majority of the Czech Republic’s total imports from the Federation of Russia.

We can however see a decreasing trend of imports from Russia since 2018, but this trend is not only focused on natural resources; it is general to all sectors and it will surely continue in its decline in sight of the recent events in Ukraine. The net import/export balance in 2018 and 2019 were largely negative for the Czech Republic, and shifted to a positive one in 2020. Moreover, in 2019, the 77 576 million CZK of natural resource imports accounted for 67% of total Russian imports. In 2020, 60% of Russian imports represented only 43 414 million CZK. This goes to show that generally, imports of all sectors from the Federation of Russia have been drastically decreasing since 2018 for the Czech Republic.

Can we be 100% independent from Russian natural resources?

Can we be independent from Russia’s gas and petroleum and get our supplies from somewhere else? This is the question that every European country is asking themselves at the moment, and even though it seems to be quite simple in theory, it is much harder to put into place.

In light of the heavy dependence of European (especially eastern) countries on Russian gas and petroleum, the complete stop of Russian natural resource supply would be very difficult, if not impossible, for the European Union. In the hypothesis of a complete stop of Russian supply, natural resources would become scarce in Europe, leading to a sharp increase of its price and a change of everyday habits for the European population.

In parallel, cutting off Russia as our supplier would lead to severe economic consequences for the gas-supplying giant. In fact, Europe purchases over 45% of total Russian gas and petroleum in 2021, making them Russia’s biggest partner and source of income. Losing European dependency to their resources would leave Russia with a 158,5 billion euro (2021 EU natural resource imports) gap in their economy.

Gas supply is particularly useful when faced with cold winters for, in the Czech republic, half of the country’s natural gas is used for heating. According to the 2019 ERO yearbook, in the Czech Republic, 61% of gas was used in industry and 25% in households. An opportunity to reduce global gas consumption is therefore possible if everyone participates in their own way. We offer some advice on how to reduce your gas consumption, whether it be in your office or in your home, to face the inflation prices and the limited amount of natural gas available in Europe.